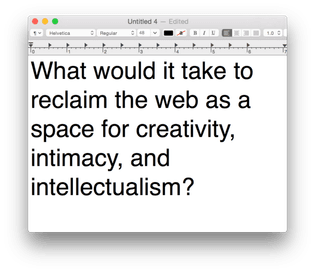

Digital media has done away with the very thing that created our sense of history: imperfect memory. The process of creating a historical narrative (or any story, for that matter) involves discarding an enormous amount of information. It’s like chipping away at a big block of marble until you’re left with a captivating statue. Forgetting is a feature, not a bug. It makes us feel like we’re moving forward through time, rather than standing still or running in circles. My grandmother and her ancestors knew this all too well. Artful forgetting, editing, and curation allowed them to craft narratives that helped their children understand the past and orient towards the future. The internet has undercut these time-tested practices of inter-generational knowledge transfer. It’s like an all-knowing god without any rituals of forgetting or forgiveness.

Faced with the inhuman prospect of total recall, we feel our only recourse is to turn to algorithms that help us sort through it all. But the algorithmic black boxes that power our media platforms work very differently than the memories we were born with. Our memories evolved to surface emotions, stories, and information from the past that might help us survive. We don’t have complete control over what we remember and when — there’s a subconscious system that “finds” old memories and “projects” them onto our mind’s eye.

In many ways, social media’s recommendation algorithms are an externalized version of this mysterious inner search process. But they’re not optimized to help us survive; they have a financial interest in prolonging our state of timeless confusion. Even the visual design of these platforms seems hell-bent on disorienting us: content that was published yesterday looks the exact same as content that was published a decade ago. In digital environments, there aren’t many signs of “decay” or the passage of time.

https://aaronzlewis.com/blog/2020/07/07/the-garden-of-forking-memes